The sixteenth century Rajon ki Baoli, or Well of the Masons. Built in the final years of the Delhi Sultanate, it's Delhi's most ornate step-well, and one of the main attractions at the Mehrauli Archaeological Park.

The Mehrauli Archaeological Park is perhaps Delhi's best kept secret. Containing ruins which, if one counts the foundation of the Hindu Rajput fort which underlies the whole area, date anywhere from the 8th to the 19th century, and encompass virtually the whole history of Islamic Delhi and then some, the park is among the very most fascinating places in the whole city. What's more, it's practically unknown.

The park is essentially a part of the same complex of Islamic ruins that Mehrauli is world famous for: The Qutb Minar, Quwwat-ul-Islam Mosque, Alai Darwaza, ect. ect. These monuments make up the UNESCO Qutb Minar World Heritage site, and they are the most visited tourist attraction in all of India, even beating out even the Taj Mahal (I'm sure because of their close proximity to an international airport) by a significant margin.

But the World Heritage site is only the core of a much larger complex, most of which goes unnoticed by the millions of visitors that come to the Qutb Minar each year. There would appear to be multiple reasons for this: First off, so many of the visitors who come to the Qutb Minar seem to be rushing through, and whereas the monuments in the World Heritage Site are very closely packed, you have to do a bit of walking in the wilderness to get much out of the Archaeological Park. Also, both of the entrances to the Archaeological Park are tough to spot, with one even being scenically located next to a garbage dump, presumably to weed out the easily discouraged.

However, it's the Archaeological Park's obscurity that makes it such a different experience from visiting the World Heritage Site: There are very few places left in Delhi that are so abounding in things to see and yet so completely uncrowded. I've visited three times (the first time, I forgot my camera, the second, I took the photos you see below, and the third, I took my girlfriend), and I only once saw other foreign tourists, and only two at that.

The park is best visited on foot, and can be quite easily accessed from the Qutb Minar Metro Station. After you leave the station, on the Qutb Minar side, walk across the road, turn right, then turn left after maybe 15-20 minutes of walking, and you're there. However, not all the sites worth visiting in the area are in the park proper, and there are a few interesting places to see along the way.

Madhi Masjid. As I was walking north from the metro station to the Mehrauli Archaeological Park, on a lark, I happened to take a left turn down a small side road, and after maybe five minutes, quite unexpectedly stumbled into this old mosque. There was no signage at the site, and it was actually only after I came back to America that I learned it was called the Madhi Masjid (and I'm not sure if "Madhi" is in fact just a different spelling of "Mahdi" ). It was apparently built during the Lodi Dynasty of the Delhi Sultanate (the last line of Islamic rulers in Delhi before the Mughals). Other than that, I've been able to uncover very little other information about the Masjid....note the big bird I accidentally caught in the upper left-hand corner...As an aside, there's a short passage on this mosque in my old Eyewitness Travel Guide from 2002, which states that it dates back to 1200, which I don't believe for an instant, unless the current masjid was rebuilt on the site of a much earlier structure, but it goes to show just how sketchy the information on this building is. Incidentally, the Eyewitness Travel Guide was the first book I ever got that dealt solely with India, and, occasional factual errors aside, it provides a very good introduction to the country...

The Qibla Wall of the Madhi Masjid, with a little bit of fading tile work.

Backtracking to the main road from the Madhi Masjid, and then heading north for about 15 minutes, one comes to the small, rather insufficiently signed entrance to the Mehrauli Archaeological Park proper. Taking the first right immediately after one enters the park, you come to one of the most historically important Islamic Mausoleums in all of India: Balban's Tomb, along with a number of crumbling adjacent structures.

Balban was the last effective ruler of the Mamluk Sultanate, the first line of Islamic rulers who made Delhi their capital. Like the initial Mamluk rulers in Delhi, Balban was a slave of Turkic origin. The word Mamluk, though it's usually translated simply as "Slave" seems to mean something rather more like "Soldier-Slave," an institution that existed throughout the Muslim world. Mamluks quite often rose to the ranks of generals and governors, becoming slaves in name only, and were thus frequently capable of carving out their own independent kingdoms.

In Balban's case, he was purchased as a slave by Illtutmish, the third, and perhaps most illustrious ruler during the Mamluk period (he also built the Sultan Ghari, India's first Islamic tomb, which I devoted a whole other blog post to). Balban worked his way up in the Mamluk administration, first becoming the prime minister, and later Sultan, of the kingdom, which was in decline during the middle part of the 13th century. Balban, after assuming the throne, managed to stabilize the sultanate, and gave the Mamluks their last gasp of prosperity. He is remembered as something of a tyrant, establishing a secret police network and demanding that his subjects prostrate themselves in his presence, a practice which hadn't been followed by his predecessors. However, he also effectively defended the Sultanate from the threat of the Mongols, and allowed an assortment of Muslim Turks, Persians, and Arabs from the conquered lands to the north to take refuge in his kingdom. He ruled competently, if heavy-handedly, all the way into his eighties, but his successors failed to live up to him, and the Mamluks were swept away not long after his death.

What makes Balban's tomb and the adjacent buildings so important is that they appear to have been the first structures built in India using true arches. It can be said that Balban's tomb laid the foundation for all of the later, more famous, Islamic monuments in India, and therefore for a fair number of the most exquisite architectural achievements in history.

However, despite the tomb's immense historical importance, I visited three times and never saw anybody else there (other than my girlfriend Aneesha, that is). The mausoleum, which includes not only Balban's tomb, but also a line of crumbling, forgotten graves, seems deserted and forlorn. In fact, the site was discovered only in the mid twentieth century, after which it was pieced together that the tomb was in fact that of Balban.

Looking through a small, and recently restored (at least up to a point) gateway. The rather modest gateway is itself important in that it is the oldest surviving building in India with a true dome, though evidently the Archaeological Survey of India had to restore the building fairly heavily to make it look like much of anything. The building in the background is Balban's tomb.

Looking through what remains of Balban's tomb. The building has the look of something that was lost in the jungle for hundreds of years...it was apparently only cleared of vegetation sometime in the last few decades.

Inside what was once the tomb's domed chamber, thought the dome has long since fallen away. The building you can see through the arch is the heavily restored gateway from above. Though from outside it appears to be topped with a pyramidal structure, apparently the ceiling of the gateway is actually India's first surviving dome, if rather an unspectacular one.

Balban's grave. Large parts of the gravestone seem to have been worn off by the elements and then rather haphazardly placed back on top. Still, there are a number of other graves in the vicinity that are in even worse condition, and look like little more than piles of dirt with bits of broken red masonry sticking out of them.

Old, worn inscriptions in Arabic lettering on the side of the grave, with oil applied to them to make them more legible.

Balban's grave and creepy old walls.

This was a curious bit of business. Everywhere else on the exterior of the tomb, the layer that once covered the underlying rubble cement had long since been scraped away. This one small patch of Arabesque stucco work, and the even tinier bit of tile next to it, are all that remain after over seven centuries of the tomb's outer covering. It's interesting to speculate what the tomb might have looked like in its day. I'm sure that it would be almost unrecognizable, particularly if there really was bright blue tile work all over it.

Directly adjacent to Balban's tomb is a large expanse of ruins probably dating from the sixteenth and seventeenth century. The ruins are clearly residential structures, and together they make up something of a small ruined city. They were only cleared of vegetation back in 2000-2001, and the structures on the fringes of the settlement are already in the process of being swallowed back up by scrubby Delhi overgrowth.

Delhi Dog. There was a whole little community of pups in this particular tangle of ruinous rubble cement, though this was the only picture that I took which turned out.

Looking over the landscape of ruins next to Balban's tomb.

On the other side of the ruined settlement are the Jamali Kamali Mosque and Tomb, which together make up the focal point and most visited attraction in the park.

The Jamali Kamali Mosque...yes, the trees do rather the spoil the composition, but it's a beautiful spot nonetheless. The Jamali in "Jamali Kamali" was a Sufi saint and court poet during both the late Lodi and early Mughal period. He evidently survived into the rule of Humayun, the second of the great Mughals. The Kamali in "Jamali Kamali," however, was evidently someone important, who was associated with Jamali, but who exactly he was, or what he did, is lost to history. I've heard, from various sources, that Kamali was either Jamali's friend, brother, teacher, co-court poet, homosexual lover, or that "Jamali Kamali" is actually just one person...and I frequently got different explanations from the same person...in short, I don't really know who Kamali was.

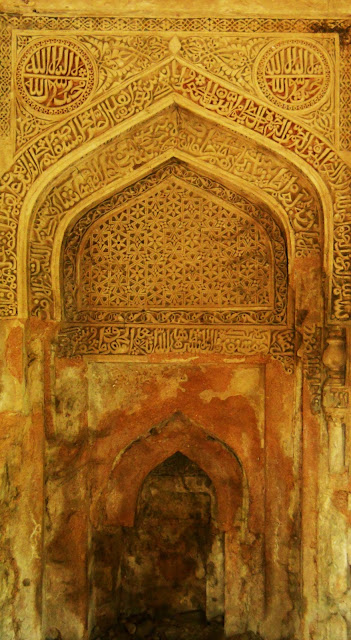

The central mihrab in the Jamali Kamali Mosque. Both the Jamali Kamali Mosque and tomb are notable as being some of the very earliest examples of Mughal architecture, given that construction on them began only two years after the establishment of the dynasty in Northern India.

A secondary prayer niche in the Jamali Kamali Mosque.

This is the Jamali Kamali tomb, which is located in a small courtyard directly adjacent to the mosque. Note the Qutb Minar to the left. The tomb, which was apparently designed by Jamali, looks rather plain from the outside. To go inside, you one has to engage one of the caretakers at the sight, who do expect a small tip (rs. 40 seemed more than sufficient), though in my experience the caretakers weren't pushy at all.

Inside Jamali Kamli tomb. I do believe that the interior of the tomb, though tiny, is perhaps the most beautiful single room in Delhi, and one of the very greatest sights in the whole city...fairly amazing given that it's virtually unknown, and the only cost involved is the small tip for the caretaker.

A different view, looking up at the ceiling of the tomb.

One of these, in the Jamali Kamali tomb.

To the left of the Jamali Kamali Mosque, there is an enclosure containing a number of small, but very unusual, ruins. As I recall, there's no sign next to them, though I later learned, again after I returned to America, that the ruins are associated with a certain Khan Shahid, one of Balban's son. That means that they date from the late 13th century, the final years of Mamluk rule in Delhi.

A pavilion in the Khan Shahid's Tomb enclosure, which has protected a number of exquisite works of art for seven centuries on the underside of its roof. I really have no idea what the purpose of this pavilion was, though it's situated right next to Khan Shahid's tomb.

Faded, crumbling, plaster calligraphy and arabesque, on the ceiling of the pavilion.

More faded inscriptions and arabesque. Someone seems to have been lighting fires under the pavilion....it took quite a bit of fiddling with the contrast on my computer to make these pictures look like anything at all.

In Khan Shahid's Tomb proper. The tomb itself is in fairly poor condition, though quite a bit of calligraphy and plaster work has survived above the western entrance.Seeing what remains of the outer coverings of Balban's son's tomb, one wonders why the outside of Balban's is almost completely bare...It may be that the outer layering was stripped to provide materials for other, nearby structures (something which apparently happened quite frequently in Delhi.)

A road leads ahead from Khan Shahid's Tomb, towards a Lodi period mosque and a couple of tombs. To the left of the road are a number of totally unexcavated structures.

Two creepy, mostly buried arches. There are quite a few structures in the park which seem not to have attracted any attention at all from the Archaeological Survey of India...from what I've seen, the woods in the area are full of the disintegrating, forgotten, remains of buildings from the last 1300 years. Unlike so many parts of Delhi which seem completely picked over, it seems to me that there's still probably lots of archaeology still to be done in this corner of the city.

Mughal Tomb. This was rather puzzling. About a three minute walk from the mostly buried arches are two tombs. Signs say that they're from the Mughal period, and that's about the only thing I know about them. I would guess that they're early Mughal, but I don't know that for sure. The sign you can see in this picture mostly talks about the conservation measures recently employed to keep the tomb from falling apart. I'm glad the Archaeological Survey of India decided not to let it crumble away into nothing, but now that the building has been restored, for some reason they allow it to be used as a storehouse for construction equipment, sand, and spare signs, and they don't seem much bothered by the trees it's got growing out of it.

Dilapidated Mihrab. This is in the other Mughal Tomb, which is partially buried. I suspect that the reason only half of the decoration on the Mihrab remains is because it was at one time partially covered in moist, moldy earth, though I don't know that for a fact.

Circular decoration (I don't know the technical term) on the underside of the dome in the Mughal Tomb. Unlike most of the interior of the tomb, the top of the dome seemed fairly well preserved.

Starting at about the Mughal Tombs, the develops a rougher, far less well-maintained atmosphere. The western edge of the land set aside by the Archaeological Survey of India butts up against the congested urban village of Mehrauli, and the urban area seems to be sort of bleeding into the archaeological park. The result is much more trash, along with increasingly worried looking vegetation and lots of wild pigs. There are still signs and trails laid out in this part of the park, but the few security guards in the area seem only interested in keeping up the immediate surroundings of the most famous structures, and not the grounds as a whole.

The exact demarcation between Mehrauli Village and the park is hard to determine. Even after you've wandered out of the woods, you still see lots of ruins and Archaeological Survey of India signs. Also, the trees don't stop all at once, but sort of fade out....there's a couple of large patches where there's so much trash on the ground that plants aren't able to grow properly....It's the sad side of the Mehrauli Archaeological Park.

At one point I wandered onto the streets of Mehrauli, just to see what there was to see, and came across the Gandhak ki Baoli, which is usually lumped in with the Archaeological Park, though it's actually surrounded on all sides by the urban area.

Gandhak ki baoli. Gandhak means sulfur, which the waters of the well are said to have once smelled like. The step-well was dug during the reign of Iltutmish, the third ruler of the Mamluk Dynasty of the Delhi Sultanate, in the early decades of the 13th century. Apparently the well used to be the local swimming hole for the children who lived nearby, but the powers that be, spoilsports that they are, closed it off.

A view of the back of the well from about water-level. The well comes from the very earliest phase of Islamic rule in India, and the architecture reflects this, as there are no true arches, and the pillars are reminiscent of Hindu temple columns (in fact, the pillars might very well be from temples that were destroyed by the Muslims, and then reused for the purpose of building the well.) In this picture, another two and a half levels of the well are submerged.

Not far from Gandhak ki Baoli, back under the trees, are a cluster of much later, Lodi period (15th-16th century) structures, most of which, unfortunately, are rather too trash-strewn to be photogenic. Nearby is another, more architecturally advanced step-well called Rajon ki Baoli, which means, roughly, "the Well of the Masons."

Rajon ki Baoli, Delhi's most ornate step-well, and quite a contrast from the simplicity of Gandhak ki Baoli. The structure dates from the early 16th century. The well has been fairly heavily renovated of late, though not enough to detract from the overall experience of visiting it. Note the large boulders on the left, sitting on top of the second tier, that have been incorporated into the architecture. After the Jamali Kamali Mosque and Tomb, this is the most visited site in the park, for obvious reasons.

What makes Mehrauli such a fascinating place to visit is that the area exhibits a very densely layered series of historical stratum, beginning with the Rajput bedrock, continuing through all five dynasties of the Delhi sultanate in quick succession, and then encompassing the long period of Mughal rule. However, the uppermost, and perhaps most bizarre, strata is that which was laid down by the British in the 19th century. Sir Thomas Theophilus Metcalfe, who served as the British East India Company's man in the later Mughal court, made his own eccentric additions to the historical landscape of Mehrauli, which included converting a Mughal tomb into a weekend retreat, constructing English style gardens and guest houses, and enhancing the view around his new projects by creating, as it were, whole new ruins, which are referred to as Metcalf's Follies.

A folly is a newly built structure that is meant to look like an ancient ruin. They were quite fashionable in Europe in the 18th-19th century, where gardens and estates would be enhanced with fake temples, pagodas, pyramids, and assorted false exotic ancient constructions.

In keeping with this rather eccentric custom, Charles Metcalfe, upon buying the the tomb of a certain Quli Khan and land which surrounded it from the Mughal court, improved the view around his new acquisitions by building a number of quite large, and rather bizarre, quasi-Islamic monuments, employing the same rubble-construction techniques that had been used over the last seven centuries. Though Metcalfe was apparently no great friend of the Indians themselves, he was known to love India's architectural achievements, even to the rather odd extend of using a Mughal tomb as a weekend retreat.

But Metcalfe's follies, unlike their European counterparts, were built right in the midst of the actual ruins that had inspired them in the first place. Now the follies are largely forgotten, and being over 160 years old, one can say that the counterfeit ruins have undergone sufficient neglect to be considered actual ruins. Just as virtually every other line of rulers in Delhi built monuments in Mehrauli, so too did the British, albeit very strange ones.

The 17th century tomb of Quli Khan, the brother of one of emperor Akbar's generals, which Metcalfe converted into a guesthouse. The tomb is in itself rather a graceful piece of architecture. The outside was once partially covered in multicolored tiles, of which only a few scant traces remain. Metcalfe added two annexes to the building, of which only one, which you can see to the left of the picture, remain. He renamed the tomb Dilkusha, which means something along the lines of "The Hearts Delight." Apparently the whole area around the tomb was converted into something of a high end resort, complete with a man-made lake for boating, and the tomb was often rented out for weddings.

The interior of Quli Khan's tomb, which Metcalfe seems to have had the sense not to mess around with.

Metcalfe's canopy, which was meant to mimic a Chhatri, or umbrella shaped pavilion, which are common in Indian architecture from after the introduction of true domes. This is actually just outside the Jamali Kamali Mosque, though it seemed to belong to this part of the blog post. I suppose that Metcalfe thought that this particular hillock was insufficiently topped. Though the actual dome doesn't look like anything either the Delhi Sultanate rulers or the Mughals would build, the pillars that are holding it up do look like actual Hindu temple columns, and I wonder if they're the genuine article.

Metcalfe's Folly Fish. This is on the underside of a folly Chhatri in front of Quli Khan's tomb. This rather gives away the structure, as no genuine Islamic building would have depictions of any sort on it (not even of small fish).

Metcalfe's Much Defaced Fireplace, in a small secondary guesthouse he built a short distance away from Quli Khan's Tomb.

Metcalfe's Mesoamerican Step-Pyramid. One of his follies. Though the constructions methods were made to match those of the nearby Islamic monuments, no Muslim ruler of Delhi would build anything like this. This is just outside the Archaeological Park, across from the parking lot for the Qutb Minar Complex. It once could be seen from Quli Khan's Tomb, though now the view is obstructed by trees.

Metcalf's Giant Screw-Like Ziggurat Thing. No one but an eccentric early 19th century Englishman would build something like this.

I was surprised to find that there was still a place in Delhi which had so much to see, and yet was so comparatively unexplored. It seems as though roughly 99% of the visitors to the Qutb Minar pass by the Mehrauli Archaeological Park without even noticing that it exists. This is, of course, one of the reasons for going: There are few places in Delhi where one can see such fantastic things without being part of a giant crowd. There's practically no hassle in this rather large expanse of south Delhi, and I imagine that visiting it is rather like what visiting the rest of Delhi must have been like years and years ago, before international tourism sprang up in a major way in India. There is an undiscovered vibe about the whole area, while the individual things to see are at least as interesting as those in the World Heritage Site next door, if a bit more spread out.

I have no doubt that the park will increasingly be on visitor's radar in the coming years. Certainly, in looking the area up online, I've noticed that most of the articles written about it come only from the last few years, or even from the last few months. I know that, as little as ten years ago, the ruins around Hauz Khas were similarly undiscovered, though now they're swamped with canoodling couples and upscale white tourists. The Archaeological Park will almost certainly share a similar fate in the next few years.

However, I have encountered a few rumors online suggesting that the Archaeological Park may simply get incorporated into the World Heritage Site. If that were to happen, it's true that the area would almost certainly see vastly more visitors and thereby lose its undiscovered feel. But it would probably also be better looked after, and the historical structures would survive longer into the future...which is ultimately more important.

That all being said, The Mehrauli Archaeological Park is Delhi's historical last frontier, and the time to visit is now.

Sleepy dog in the Qutb Minar's shadow.

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.